Clubhouse – our worst hangover yet!

Clubhouse is not the origin of all evil when it comes to compromising user privacy and the grave consequences of it. But, in the times we live in, where privacy became a household name and a recurrent legal and PR problem for established platforms like Facebook and Google; and with the presence of milestone regulations like the GDPR; one must wonder why would an emerging platform not only disregard all of the above, but also push the problem further in the wrong direction. Even from a business perspective, it does feel like Clubhouse did their market study based on data acquired from ten years ago. It only takes one look at the millions of users that WhatsApp lost this past January after an unfortunate change to their terms of service, to see that users have made a giant leap of awareness around data privacy. This also showed how readily available the alternatives are nowadays. Competitors who invest in privacy, like Signal and Telegram, were ready to welcome the mass migration which forced a giant platform like WhatsApp to backtrack.

Paul Davison one of the two founders of Clubhouse is behind the infamous Highlight app which among other issues was a nightmare for user privacy and safety. In 2020, an ex-employee of Highlight told Verge that Davison’s “entire perspective was always to push for, how do we get users to expose more data in the product?” and that “user trust and safety was completely an afterthought.” At least, we know that Davison is consistent.

Putting the marketing illusion of exclusivity aside and the fact that the last thing the world needs is another Social Media, Clubhouse stirs curiosity. As a sound enthusiast, I decided to join and check it out.

In order to be able to invite people across the door of exclusivity – assuming they own an iPhone – one has to grant Clubhouse access to the contact list. Upon doing so, Clubhouse recommends names to be invited, under which you can see how many contacts that person has who are already Clubhouse users. These are shadow profiles, data about users who didn’t submit it themselves but that we volunteer to Clubhouse (and its wide web of servers, governments and third party corporations). Joining Clubhouse and using its features is not only about one’s own data, but also the data of everyone on our phones. Shadow profiles in addition to users’ data, can be used to map social and political groups, networks, of racialized communities or individuals, or of people whose identities or beliefs are criminalized or which are of interest to authorities, corporations and adversaries: BIPoC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour), LGBTIQ people, activists, Human Rights Defenders… etc.

Clubhouse is a voice-based platform & our voices reveal a lot about our emotional and mental state. They can reveal our background, social class, and even personality traits. Our accents, our dialects, the expressions that we use, all tell our stories and the stories of the communities we belong to.

Clubhouse says that “the experience is more like a town square, where people with different backgrounds, religions, political affiliations, sexual orientations, genders, ethnicities, and ideas about the world come together to share their views, be heard and learn.” In the rooms I joined I noticed a certain sense of comfort among users. Which at a first glance is reassuring. Hearing familiar voices, especially in small groups, and especially at night, created an atmosphere of familiarity and intimacy. This led some users to share intimate details about their sexualities, personal stories and advice on migration and asylum seeking, and political debates around sensitive topics. I was terrified for this had to be properly relayed over secure encrypted servers, and within safety measures like knowing who is listening and if they can record what is happening. I dug in Clubhouse’s data use policy (aka privacy policy), and I checked what one can and cannot do on the app.

The platform, like many, is very ambiguous about how they store our data, and who they share it with and what for. Clubhouse uses servers based in the US which remains short on data protection especially with the extended reach of agencies like the NSA. The app also uses the Shanghai-based startup Agora for its real-time voice and video engagement. Being based in Shanghai and under Chinese jurisdiction, Agora is legally-bound to comply with the regulations of the Chinese government. Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO) revealed that Agora’s backend infrastructure receives packets containing “metadata about each user, including their unique Clubhouse ID number and the room ID they are joining. That metadata is sent over the internet in plaintext (not encrypted), meaning that any third-party with access to a user’s network traffic can access it. In this manner, an eavesdropper might learn whether two users are talking to each other, for instance, by detecting whether those users are joining the same channel.” This raises serious concerns about the privacy and safety of users discussing issues that the Chinese or the US government consider a threat.

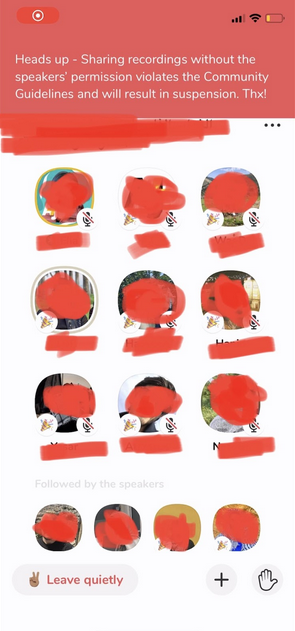

This past weekend (February 21st), a user managed to connect a Clubhouse API to his website, and broadcast the audio chats from various rooms in the app. Clubhouse confirmed the spillage to Bloomberg and stated that they suspended the user which violated the platform’s terms of service. Nevertheless, and using the simple screen grab feature of the iPhone (which Clubhouse so far is strictly built for), I managed to record whatever room I wanted to. Clubhouse did warn me that posting it without users’ consent can result in suspension. But how would they know what I could do with the recording? They can’t. Were the users informed that someone was recording their conversation? No (I asked some of them). Is it only about sharing the recording? Definitely not. An adversary be it a repressive regime, an intelligence agency or a hate group can employ the recording for a myriad of threats.

Screenshot of the video recording from a Clubhouse room. The recording was deleted after testing.

Clubhouse started with an alerting disregard to user safety which journalist Taylor Lorenz documented through her own experience on the platform. This was followed by various reports about the platform being used to spread racism, antisemitism, misogyny, and a barrage of conspiracy theories.

It all boils down to Clubhouse’s lack of understanding, premeditated or not, informed or not, about the risks of running such a space with such an infrastructure and such basic mistakes.

Who starts a social media platform in 2020 without a block or mute button (though this important feature was added later on). The platform makes commendable statements against abuse in their terms of service, yet it still falls short on the mechanism to address user safety and the process for accountability when there is abuse. Though they claim to address “incident” reports of abuse swiftly, the process raises serious questions. Upon an “incident” report, the platform will keep a “temporary audio recording” which is retained “for the purposes of investigating the incident, and then delete it when the investigation is complete.” Sounds good on paper, but what happens when a for-profit platform, that has major issues with data privacy, transparency, and an alarming infrastructure; is the investigator, the judge and the enforcer of the sentence? And on top of it, they will delete the evidence when they themselves deem the issue settled. Of course, this is not a call to record and document what is being said on the platform. This is to inform the users, and to highlight Clubhouse’s lack of the vision and knowledge that are crucially needed to address such complicated and dangerous issues. Problems other platforms with much longer experience and a wide array of scandals have been struggling with for years.

Finally, the platform doesn’t provide an easy and accessible option for users to quit. It is closer to entrapment. I wish I was told before I joined that there is no “delete account” button, let alone an easy way. Rather, users are thrown into a Kafkaesque process where it is not clear when I can be freed, how long that will take, for how long they will keep my data, and meanwhile where it will be stored and what for.

For now, I am stuck. Meanwhile, I will keep silent in the Club. I will not give Clubhouse any access to anything I can control on my phone. From inside the Club I can tell you, if you are still standing outside, think twice before coming in. It is a nightmare as it is, but it has the potential of spiraling into a much worse nightmare.

Leil Zahra is a transfeminist queer filmmaker, researcher and trainer on digital security and data privacy, born in Beirut and based in Berlin. Their work has a major focus on migration, anti-racism, decolonialism, queer politics, and social justice.

Read more: